E.coli in dogs and cats – friend or enemy?

E.coli are normally friendly bacteria that form part of the complex microflora in the gastrointestinal tract enjoying a symbiotic relationship with the host, but certain E.coli can cause gastrointestinal disease. Molecular detection of pathogenicity genes using our PCR tests, detects enteropathic strains of E.coli that can be an important cause of diarrhoea in dogs and cats, but are overlooked in routine faecal culture. We also produce oral autologous E.coli vaccines as an adjunct to treatment, and these have been used successfully to manage a spectrum of chronic gastrointestinal diseases.

Types of enteropathic E.coli

Enteropathogenic E.coli (EPEC) appear to be the most common type of intestinal pathogenic E.coli in dogs and cats and can cause both acute and chronic diarrhoea. Pathogenicity involves an “attaching-effacing” mechanism that strips microvilli from enterocytes resulting in osmotic diarrhoea due to compromised absorptive function, illustrated here:

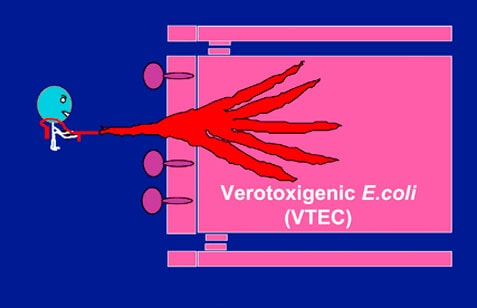

Verocytotoxin-producing E.coli (VTEC) secrete verotoxins, now known as Shiga-like toxins (Stx1 and Stx2) reflecting similarities with toxins produced by Shigella, and may be called Shiga-toxin-producing E.coli (STEC). These cytotoxins are lethal to intestinal epithelial cells, and can cause haemorrhage and ulceration, potentially mimicking the severe enterocolitis caused by invasive bacteria.

Enterohaemorrhagic E.coli (EHEC) are the best known VTEC subgroup which includes the zoonotic VTEC 0157 found in ruminants. EHEC not only secrete Shiga-like toxins, but also cause attaching-effacement of microvilli like EPEC. There are reports indicating that VTEC can cause intestinal disease in dogs, but VTEC 0157 has very rarely been isolated.

Enterotoxigenic E.coli (ETEC) do not cause intestinal damage, but secrete heat-labile (LT) or heat-stable (ST) enterotoxins. These toxins have a specific biochemical effect on the intestinal mucosa, acting as secretagogues resulting in an acute watery electrolyte-rich diarrhoea. ETEC have been reported in dogs, but incidence appears to be relatively low.

Enteroinvasive E.coli (EIEC) can invade the mucosa of the distal small bowel and colon causing acute enterocolitis. Enteroaggregative E.coli (EAggEC) adhere to the intestinal mucosa without invading or causing inflammation, and are thought to cause diarrhoea by production of an enterotoxin. There is currently little evidence that either group is important in small animals. However, it seems likely that additional enteropathic strains of E.coli will be identified in the future.

All of these enteropathic E.coli can cause acute clinical disease. However, properties such as adherence to the surface by EPEC promote long-term colonisation predisposing to chronic intestinal disease.

Management of enteropathic E.coli infection

In common with other bacterial enteropathogens, identification of enteropathic E.coli in faeces does not necessarily mean that they are responsible for clinical signs. Some animals may act as carriers, and the ability to cause disease may depend on environmental factors such as stress, and an innate ability to mount an effective mucosal immune response to these organisms.

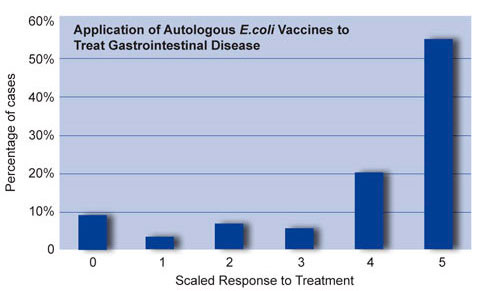

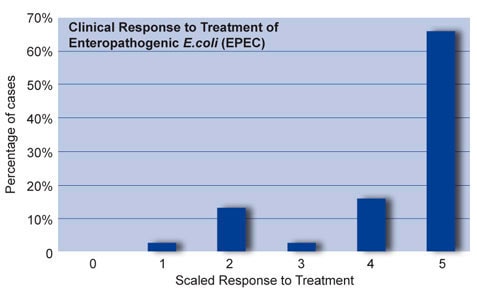

Treatment of enteropathic E.coli should be considered for positive cases with severe acute, or persistent signs of gastrointestinal disease. Choice of antibiotic should be based on sensitivity testing and may be supported by administration of an oral autologous E.coli vaccine which can be produced by BattLab on request. Support for this approach is provided by our follow-up of 38 EPEC positive dogs, most with persistent diarrhoea, more than 80% of which showed distinct or considerable improvement with treatment (scale 4 or 5).

Oral autologous E.coli vaccines have also been used successfully to help manage a spectrum of chronic gastrointestinal diseases in dogs and cats. Our follow-up of 89 dogs, most with persistent signs of gastrointestinal disease which in many cases had been present for many weeks, showed a distinct or considerable response to treatment in more than 70% of cases (scale 4 or 5).