Principles of intestinal permeability testing

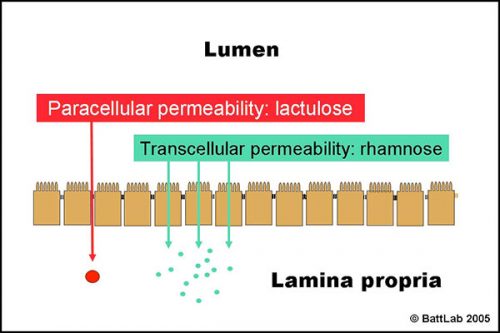

The normal small intestine is lined by finger-like villi covered by absorptive epithelial cells which form an effective barrier between the lumen and the lamina propria. Figure 1 shows two potential routes for passive transfer of molecules across this barrier:

- PARACELLULAR permeability between epithelial cells is normally low as tight junctions form effective seals to keep out larger harmful molecules eg toxins

- TRANSCELLULAR permeability through epithelial cells is normally high as this route allows absorption of small nutrients eg glucose

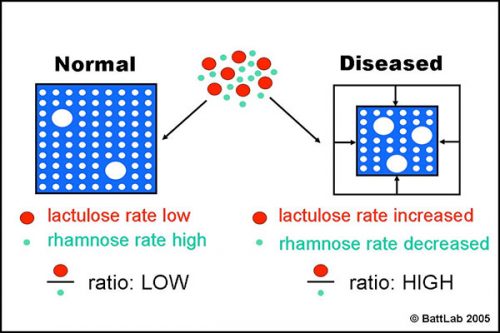

Figure 2 shows how the ratio of lactulose (paracellular) to rhamnose (transcellular) detects small intestine damage. Interference with tight junctions results in increased permeability of lactulose, whereas loss of microvilli or villi results in reduced surface area and decreased permeability of rhamnose. The net result is an increase in the lactulose to rhamnose ratio in blood or urine after oral dosing of these sugars.

Intestinal permeability and dietary sensitivity

Measurement of intestinal permeability is a sensitive non-invasive technique to provide:

- justification for intestinal biopsy

- a baseline for response to treatment

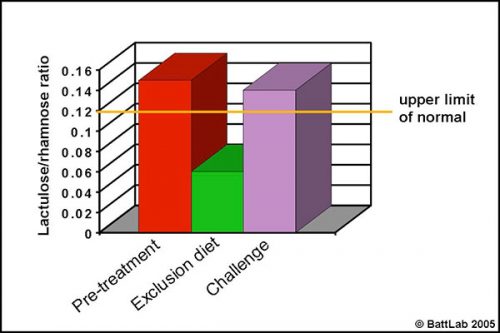

Permeability testing can help justify intestinal biopsy and may be more helpful because biopsy findings may be negative despite disease, or may give no indication of cause despite pathology eg “inflammatory bowel disease” – is it dietary sensitivity, bacterial overgrowth or idiopathic? More importantly, monitoring response to treatment can help determine the cause of damage. This is illustrated in Figure 3 which shows urine permeability tests in a 3 year-old Golden retriever. A high initial result normalised on a chicken and rice exclusion diet and reverted to a high level on dietary challenge, indicating dietary sensitivity.

Intestinal permeability and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

Permeability testing has proved particularly useful to assess the severity of mucosal damage in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and also to help long-term management.

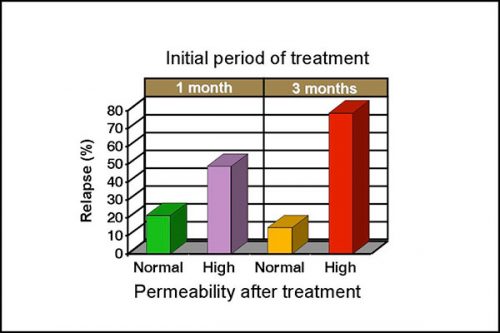

Intestinal permeability is increased in 50-60% of clinical cases with SIBO, even when there are no histological abnormalities. Normalization of intestinal permeability following 4 weeks of antibiotic therapy indicates successful repair of mucosal damage and antibiotics should be discontinued. Figure 4 shows that dogs with high permeability at that time are 3 times more likely to relapse despite an apparent clinical response to treatment, and continuation of antibiotic therapy is therefore recommended. Differences are more marked after 3 months of treatment as dogs with high permeability are approximately 8 times more likely to relapse. A persistent high permeability in dogs with a poor clinical response should prompt further investigation of underlying disease, such as a primary inflammatory bowel disease.

How to perform permeability testing

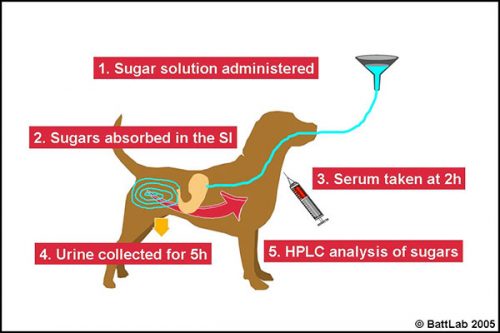

The lactulose/ rhamnose permeability test procedure (Figure 5) should be performed after fasting for at least 12 hours, and (for the urine test) ensuring the dog empties its bladder prior to starting the test. Drinking water should be added to the sugar solution up to the mark in the bottle provided – a total of 100ml for dogs up to 20kg and 200 ml for dogs over 20kg then:

- administer the solution orally – preferably by stomach tube passed in front of a tape muzzle in the gap just behind the canine tooth on one side of the mouth

- monitor for 10-15 minutes to ensure there is no vomiting – the sugars pass through the stomach to be absorbed in the small intestine

- at 2 hours take 3ml blood in serum tube(s)

- OR collect all urine for 5 hours and save a 20ml aliquot in a universal containing thimerosal (provided)

- send the spun serum or urine with preservative to BattLab for analysis.

References and further reading

- Rutgers HC, Batt RM, Hall EJ, Sørensen S, Proud FJ. (1995) Intestinal permeability testing in dogs with diet-responsive intestinal disease.

J Small Anim Pract 36: 295-301. - Rutgers HC, Batt RM, Proud, FJ, Sørensen et al (1996) Intestinal permeability and function in dogs with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J Small Anim Pract 37: 428-434.

- Sørensen SH, Proud FJ, Adam A, Rutgers HC, Batt RM. (1993) A novel HPLC method for the simultaneous quantification of monosaccharides and disaccharides used in tests of intestinal function and permeability. Clinica Chimica Acta 221: 115-125.

- Sørensen SH, Proud FJ, Rutgers HC, Markwell P, Adam A, Batt RM. (1997) A blood test for intestinal permeability and function: a new tool for the diagnosis of chronic intestinal disease. Clin Chim Acta 264: 103-115