As travel starts to open back up, we are likely to see many owners want to explore their new found freedoms with their beloved companion at their side. Our clients may also be tempted to take on a rescue from another country. Whatever the scenario, as the demand for companion animals continues to rise and changes in travel restricts ease, it is likely we will see more pets entering our shores with infectious diseases that are not endemic in the UK.

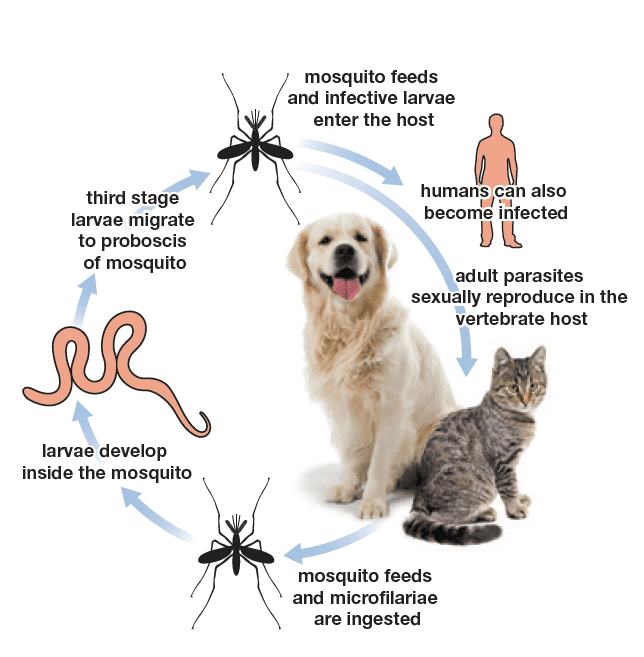

This month we are focusing on Dirofilaria infections, vector-borne parasitic diseases affecting dogs, cats and wild carnivores. There are two types of infections caused by two different nematodes, namely D. immitis and D. repens. These have similar life cycles, summarised in the picture below.

Picture 1: Filarial nematodes life cycle. From ESCCAP Guidelines.

D. immitis is found across the world and is responsible for heartworm disease, a potentially fatal disease caused by adult worms located within the pulmonary arteries and later the right side of the heart. In dogs, early clinical signs can include chronic cough which may be followed by moderate to severe dyspnoea, weakness and sometimes syncope after exercise or excitement. Often, it evolves into congestive heart failure characterised by ascites, oedema and sometimes the so-called “caval syndrome”. In cats, symptoms are more variable, ranging from to acute dyspnoea to sudden death.

Diagnosis of D. immitis can be carried out with direct examination of a drop of whole blood (although this method is scarcely sensitive, as microfilariae are not always present in the peripheral blood), modified Knott test (detection of microfilariae in blood after concentration), ELISA antigenic test or PCR, which also allows species identification.

D. immitis is potentially zoonotic, although very few cases of human disease have been reported. Most importantly, it can be spread from a reservoir dog to other dogs in the presence of the vector (mosquitos belonging to the Culicidae family) and climate conditions, especially in southern England where conditions are becoming increasingly more hospitable to mosquitoes, posing a risk for dogs not travelling abroad. Therefore, it is important to carry out prevention against heartworm when planning on travelling to endemic areas.

D. repens is endemic in Europe and can cause either undetected infections or cutaneous disorders. Clinical presentation may vary from non-inflammatory subcutaneous nodules containing the parasites, not painful and mobile, to cutaneous swelling and itching.

Diagnosis of D. repens may be performed by cytological examination and/or histopathology of skin nodules, morphological and molecular identification of adult parasites and detection and identification of microfilariae circulating in the peripheral blood by concentration methods.

D. repens is the principal agent of human dirofilariasis in the eastern hemisphere and canine infections have also been increasing in the last decades. There is scientific evidence that D. repens has been spreading faster than D. immitis from endemic to non-endemic areas, likely due to the rate of undiagnosed dogs continuing to perpetuate the life cycle of the parasite, combined with climate changes affecting mosquito vectors and the facilitation of pet travel.

ESCCAP recommends that dogs and cats travelling from non-endemic to endemic areas should be protected against adult filarial infections. They should be treated within 30 days of arriving in the risk areas with preventative drugs. A good preventive strategy may be combining the use of heartworm preventatives with repellents during the heartworm transmission season (from May until the end of November) to protect pets from both infection and ectoparasite infestations that often occur in the same season. For pets spending no more than one month in endemic areas, a single treatment, usually administered soon after returning home, is sufficient to assure complete protection. In the case of longer visits, a monthly regimen should be administered. Animals with unknown history entering a non-endemic area, should receive prophylactic treatment for two months to kill potential migrating larval forms and be tested for circulating antigens and microfilariae after six and twelve months.