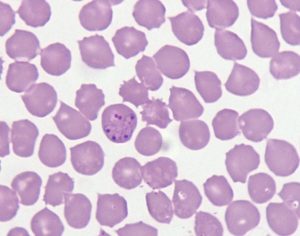

Canine blood smear of Babesia spp. showing red blood cells containing merozoites.

Canine blood smear of Babesia spp. showing red blood cells containing merozoites.

This month we are completing our short series about infections that can affect our pets while on holiday.

Babesiosis is a tick-borne disease caused by protozoan parasites, belonging to the genus Babesia, which exclusively infect erythrocytes. In Europe, four species of piroplasms have been reported to cause clinical disease in dogs, including B. canis, B. vogeli, B. gibsoni and B. microti-like. The most commonly encountered species are B. canis, associated with transmission by Dermacentor reticulatus and B. vogeli associated with transmission by the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus.

Are these vectors endemic in the UK? Foci of Dermacentor ticks had been known to be present in the United Kingdom. This tick is a proven vector of Babesia canis, which, until a few years ago was an exotic pathogen to the UK, known as a disease in imported dogs only. However, the endemic cases of B. canis recently recorded in South England and Wales in dogs with no history of travel have provided a realistic alarm bell for potentially nationwide spreading of this pathogen (Phipps et al, 2016; de Marco et al, 2017).

Rhipicephalus sanguineus is another vector for babesiosis, although less common, is not endemic in the UK. The possible risk of introduction of R. sanguineus in the UK was recently confirmed in a dog imported from Spain and another from Greece. This tick has demonstrated a high risk of local establishment, as supported by cases of unexpected B. vogeli and E. canis infections in the UK in untravelled dogs, which have been known since 2006 and 2013 respectively (Holm et al, 2006; Wilson et al, 2013).

How does the infection progress? Different species, subspecies and strains may have different pathogenicity and clinical course. Transmission occurs when Babesia spp. sporozoites are released from infected ticks during feeding, entering the dog’s bloodstream and are subsequently endocytosed by the red blood cells. The incubation period of babesiosis ranges from several days to several weeks. The intracellular replication of the organisms within red blood cells leads to intravascular haemolytic anaemia. In addition, soluble Babesia antigens can adhere to surface of noninfected red blood cells and platelets as well as infected red blood cells, leading to immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia (IMHA) and thrombocytopenia (IMT/ITP).

What are the clinical signs? Acute forms of babesiosis are characterised by moderate to severe clinical signs such as fever, lethargy, anorexia, jaundice, vomiting and in some cases haematuria. Atypical forms may be associated with haemorrhages and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with severe locomotor, cerebral, ocular, gastrointestinal and vascular disturbances due to increased blood viscosity.

Although the acute disease is more common, some animals can be chronically sub clinically infected with non-specific clinical signs such as moderate depression, intermittent fever, anaemia, myositis and arthritis and the infection may be re-activated by splenectomy or administration of immunosuppressive medications.

BattLab offers a wide variety of tests for the diagnosis of infectious diseases, including serology and PCR.

What frequent laboratory changes are seen? Clinicopathological abnormalities commonly seen include markedly regenerative anaemia due to haemolysis, thrombocytopaenia, neutrophilia with or without left shift. Because a large component of the haemolysis in these cases is immune-mediated, it is common for dogs with babesiosis to have a positive Coomb’s test and sporadic haemoglobinuria. Biochemistry changes include hyperbilirubinemia, hyperglobulinemia, and hypoalbuminemia. In some cases, the large amount of haemoglobin filtered through the kidneys can lead to acute renal disease, with azotaemia. Haemoglobinuria, bilirubinuria and granular casts can be present on urinalysis.

Can babesiosis be diagnosed with serology? Specific antibodies can only be detected from two weeks after the first infection and acute infections will therefore be missed if relying only on serology for diagnosis. In addition, sensitivity and specificity of laboratory tests are not well established. Moreover, to date, no rapid in-house tests are available.

How about blood smear examination? Is this good enough to make a diagnosis? Freshly prepared smears made from unclotted capillary blood taken from the ear pinna or the tip of the tail may yield higher numbers of parasites and can be used to reach diagnosis. Blood smear examination is very specific and will diagnose most sick dogs with Babesia canis, however it is less sensitive than PCR. This means that, if used as stand alone diagnostic tool, blood smear examination can lead to false negative results, especially if the parasite load is not elevated or if cytological evaluation is conducted by staff not used to hemiparasites.

And what about PCR? Molecular testing is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of Babesia sp. infection, and it can also provide identification of species and subspecies, important in terms of treatment options and prognosis. PCR is recommended in any patient where babesiosis is suspected but where organisms are not visible on blood smear examination. Molecular testing can be performed on EDTA blood or directly from ticks retrieved from the dog, if any.

Are there any preventive measures that should be recommended to pet owners? The risk of infection with Babesia spp. for individual dogs living in endemic areas, or for dogs travelling to or through such areas, can be significantly reduced by effective tick control. Pet owners need to be aware that preventative measures are important to protect not only their own pets but also for the health and welfare of pet populations living in the same areas.