Urine is often regarded as a stinky waste product from metabolism, responsible for yellowish stains on our clients carpets or our waiting room floors. But urine can provide us with much more laboratory information than we think, here we reconsider its role in the assessment of a patient.

Typically, we remember to perform urinalysis when our patients are presenting with haematuria, stranguria or pollakiuria or when there is a combination of polyuria and polydipsia. So, the classic approach is to submit to the lab a urine sample randomly taken from the floor or a free catch sample at best, looking for inflammation, crystalluria or bacteria that might present us with an easy diagnosis to treat the patient.

Standard urinalysis is a first screening step that provides us valuable information regarding the sediment, plus semi quantitative results for other biochemistry analytes. Urine sediment examination is also vital to diagnose inflammation, infection, detect the presence of crystals or casts, that when numerous indicate tubular damage. When urinary tract infection is suspected, urine should be collected by cystocentesis and submitted for culture and sensitivity. Despite the inconvenience of performing this procedure on the patient, this is the only way to collect a sterile urine sample, which can reliably detect the presence of true, pathogenic bacteria (rather than contaminants, that are always present even in a “clean” free catch urine sample).

Urine culture and sensitivity should also be part of the normal patient work up in cases of diabetes mellitus, hyperadrenocorticism, chronic kidney disease and ongoing immunosuppressive treatment. Speaking of hyperadrenocorticism, evaluation of urine cortisol: creatinine ratio (UCCR) can be used as a quick screening test to rule out hyperadrenocorticism given its high sensitivity. However, this test has low specificity which may lead to false positive results, in particular in case where a patient is stressed.

Proteinuria indicates renal disease and can be detected with a positive pad result. However, this needs to be interpreted in the context of urinary concentration; for example, trace of protein may be a normal finding for a concentrated urine sample but may be concerning in an animal with isosthenuric or in cases of hyposthenuric urine. Pigmenturia, very alkaline urine and some disinfectants can also lead to false positive protein results. Therefore, the best way to check for proteinuria is to measure the urine protein: creatinine ratio (UPC), which is also a criteria required for IRIS CKD staging. Unfortunately, UPC does not allow a clinician to differentiate between glomerular and tubular damage, which makes a difference in terms of prognosis and treatment. Tubular damage can reveal itself with multiple abnormalities such as glucosuria (in the absence of hyperglycaemia), proteinuria and high numbers of casts in the sediment. However, the most useful tests to evaluate tubular damage and its entity is urinary electrophoresis, which can establish if protein has a low or high molecular weight, indicating tubular and glomerular damage, respectively. A particular type of tubular damage is Fanconi syndrome, either familiar or acquired type. The latter has been associated with the consumption of “jerky” treats or can be the result of certain drug therapies such as aminoglycosides and cisplatin. A Fanconi screen can confirm the diagnosis by assessing specific amino acids excreted in the urine. The loss of COLA amino acids (cystine, ornithine, lysine and arginine) within the urine is the rationale for the diagnosis of cystinuria, a hereditary renal transport disorder affecting several pure breed dogs, and this can be confirmed with a urine sample.

Decreased tubular function can also lead to acute kidney injury (AKI) which can be reversible if it is treated promptly. The measurement of fractional excretion of electrolytes (FE) estimates electrolytes loss with the urine compared with the serum concentration, assessing the entity of tubular damage. This test requires serum AND urine collected simultaneously (spot sampling). In the past, the utility of FE has been questioned due to its high inter-individual variability, even in healthy patients. However, more recently FE has been re‐evaluated in dogs with AKI as readily available and cost‐effective markers of tubular damage and kidney function. In fact, a recent publication (Troia et al. JVIM 2018) highlighted how FE excretion of electrolytes could be a useful tool to manage AKI dogs in clinical practice.

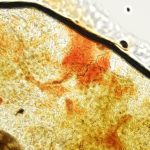

Finally, urine sediment is a precious specimen for confirmation of transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), and BRAF mutation test can be performed on a canine urine sample in a case that is not readily diagnosed with cytology (due to poor cell preservation, presence of marked inflammation etc).

At BattLab, we offer a wide range of urine testing including all the aforementioned. For more information, visit our website or contact us by phone or email.