What can be worse than a disease with non-specific clinical signs (and occasionally not even those) that can evolve into a life-threatening condition? This is exactly what we are asked to deal with, when we are trying to diagnose pancreatitis in dogs and cats. Here is a summary of the most recent literature regarding this puzzling disease and its diagnostic options.

BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CANINE PANCREATITIS

Pancreatitis is the most common disorder of the exocrine pancreas in dogs and is a common differential diagnosis for patients with nonspecific gastrointestinal signs such as abdominal pain and vomiting. This condition can be either acute or chronic, but the clinical appearance is often identical. Therefore, it can be really difficult differentiate truly acute disease from an acute flare-up of chronic disease, although this may only be important for long-term sequelae of chronic disease, such as the development of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) and diabetes mellitus (DM). The aetiology of pancreatitis is still not fully understood. It is very likely that genetic predispositions exist in dogs as CKCS, Boxers and Border Collies appear to have an increased risk of chronic disease in the UK. Pancreatitis is also commonly reported in Miniature Schnauzers as a consequence of hypertriglyceridemia. English Cocker Spaniels suffer from a distinctive form of chronic pancreatitis similar to the human autoimmune form but it’s still unproven that the disease is autoimmune. The pancreas is very sensitive to ischaemia and any condition resulting in decreased pancreatic perfusion can cause pancreatitis, and it is also a recognized complication of canine babesiosis.

AND HOW ABOUT CATS?

Pancreatitis is not very often suspected clinically in cats due to infrequent and non-specific clinical signs. Achieving a diagnosis is challenging because of limited sensitivity and specificity of most of the imaging or clinicopathological findings, particularly in relation to chronic and/or mild forms and concomitant diseases. Several studies have shown a strong association between pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Ischaemia is another recognised cause of acute pancreatitis in cats and it is particularly significant during surgery.

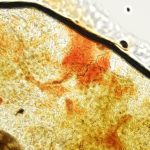

To date, the gold standard for the diagnosis of pancreatitis is histopathology, although this is often not an option. Therefore, to establish a clinical diagnosis of pancreatitis, the clinician must integrate the results of multiple tests to improve sensitivity and specificity of each of them. it’s recommended to combine signalment, history, physical examination, complete blood count (CBC), serum biochemistry, and abdominal ultrasound examination.

- CLINICAL SIGNS: Gastrointestinal signs such as vomiting, diarrhoea and cranial abdominal pain paired with apathy and anorexia can be caused by several underlying disorders. Mild pancreatitis is often overlooked but thankfully it is successfully treated like a mild gastrointestinal disorder. Evidence of systemic involvement in the disease process such as weakness, dehydration, hypovolemia, fever, tachycardia, arrhythmia, jaundice, abnormal bleeding tendency, shock or respiratory distress call for more intensive diagnostic work up.

- IMAGING STUDIES: Ultrasonographic examination of the pancreas is an option in many clinics, however, its sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of pancreatitis are operator dependent and therefore highly variable. Even if patients with clinical signs attributable to pancreatitis will still benefit from a full abdominal ultrasonographic examination to exclude other differential diagnoses, pancreatic ultrasonography findings need to be interpreted with caution, especially considering the low level of agreement between serum lipase assays and ultrasonographic variables commonly assumed to be reliable (i.e. peripancreatic fluid accumulation and mesentery echogenicity) for diagnosing pancreatitis in both dogs and cats.

- LABORATORY TESTS: Routine blood tests, including a complete blood count and biochemistry profile can in a variably percentage of cases reveal abnormalities suggestive of pancreatitis (such as inflammatory leukogram, increased C-RP or SAA, raised liver enzymes, cholestasis, hypocalcaemia). However, these changes are not unique to the disease and do not give a definitive diagnosis.

- “PANCREATIC TESTS”: None of the tests we are going to describe is 100% sensitive or specific, therefore it is possible to have a normal result in dogs or cats with pancreatitis and occasionally increased results in patients without pancreatitis.

- Amylase and lipase were used in the past for diagnosing pancreatitis in dogs and cats, but they have been dismissed due to poor diagnostic sensitivities and specificities.

More recently, several newer pancreatic lipase immunoassays and DGGR lipase assay have been developed and they are available for use in both dogs and cats. - Specific pancreatic lipase assays measure lipase molecules of pancreatic acinar cell origin and therefore it would be expected to increased only during times of active pancreatic disease.

- Spec cPL: multiple studies demonstrated that specific canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity has the greatest sensitivity (up to 71%) and specificity (100%) compared to other serological tests for detection of histopathologic-confirmed pancreatitis. As a general rule, Spec cPL sensitivity increases with acute and severe disease, whereas milder and more chronic disease lowers the sensitivity. This test is performed on serum and has a turnaround time of 1-2 days.

- Spec fPL: specific feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity is widely thought to be a useful test for diagnosing pancreatitis in cats, with 57% sensitivity and 63% specificity.As for dogs, spec fPL sensitivity depends on the severity of the disease. This test is also performed on serum and has a turnaround time of 1-2 days.

- Amylase and lipase were used in the past for diagnosing pancreatitis in dogs and cats, but they have been dismissed due to poor diagnostic sensitivities and specificities.

- DGGR lipase: in both species, this assay has shown good agreement with Spec PLI assays and can be performed on serum the very same day. DGGR lipase is already included in our Canine2 and Feline 2 profiles and has proved to be a very useful screening test. However, this test measures lipase molecules of any origin (intestinal, gastric, hepatic and pancreatic), and therefore it can be increased in association with several diseases other than pancreatitis.

- TLI measures trypsin and trypsinogen and is a species-specific test. TLI is very useful for the diagnosis of EPI (where the concentration is very low), however it can be used as an additional test in pancreatitis, although its sensitivity is very low in both dogs and cats.

- Canine TLI is quite specific, therefore an increased cTLI should be considered very likely suggestive of pancreatitis. However, Spec cPL is recommended as confirmatory test.

- Feline TLI has lower sensitivity and specificity than in dogs for pancreatitis and high fTLI can also be seen with hepatic or GI disease. Therefore, Spec fPL should always be run as confirmatory test.

FURTHER READING

- Cridge et. al. JVIM 2018. Evaluation of SNAP cPL, Spec cPL, VetScan cPL Rapid Test, and Precision PSL Assays for the Diagnosis of Clinical Pancreatitis in Dogs.

- Cridge et. al. JVIM 2020. Association between abdominal ultrasound findings, the specific canine pancreatic lipase assay, clinical severity indices, and clinical diagnosis in dogs with pancreatitis

- Haworth JVEEC 2014. Diagnostic accuracy of the SNAP and Spec canine pancreatic lipase tests for pancreatitis in dogs presenting with clinical signs of acute abdominal disease.

- Kook et. al. JVIM 2014. Agreement of Serum Spec cPL with the 1,2-o-Dilauryl-Rac-Glycero Glutaric Acid-(6′-methylresorufin) Ester (DGGR) Lipase Assay and with Pancreatic Ultrasonography in Dogs with Suspected Pancreatitis.

- Oppliger et. al. JVIM 2013. Agreement of the Serum Spec fPL and 1,2-O-Dilauryl-RacGlycero-3-Glutaric Acid-(6′-Methylresorufin) Ester Lipase Assay for the Determination of Serum Lipase in Cats with Suspicion of Pancreatitis

- Oppliger et. al. JAVMA 2014. Agreement of serum feline pancreas–specific lipase and colorimetric lipase assays with pancreatic ultrasonographic findings in cats with suspicion of pancreatitis: 161 cases (2008–2012)

- Oppliger et. al JVIM 2016. Comparison of Serum Spec fPL and 1,2-o-Dilauryl-Rac-Glycero3-Glutaric Acid-(60-Methylresorufin) Ester Assay in 60 Cats Using Standardized Assessment of Pancreatic Histology.

- Trivedi et. al. JVIM 2011. Sensitivity and Specificity of Canine Pancreas-Specific Lipase (cPL) and Other Markers for Pancreatitis in 70 Dogs with and without Histopathologic Evidence of Pancreatitis.

- JSAP 2015. Pancreatitis in dogs and cats: definitions and pathophysiology

- Zini et. al JVIM 2015. Longitudinal Evaluation of Serum Pancreatic Enzymes and Ultrasonographic Findings in Diabetic Cats Without Clinically Relevant Pancreatitis at Diagnosis.